Modular design patterns: Read models for background jobs

In any system, there are two kind of things happening:

- Things that happen directly after some actor makes some action.

- Things that happen in the background.

In this post, I’m going to show a pattern that can make background jobs more modular.

A pattern, compared to more general principles, is something that works well in a specific context. The following technique is not universal, but it’s often really useful.

Example use cases

- Send a reminder to all participants 10 minutes before an event starts.

- Finish the trial period 14 days after the user signs up.

- Ask the user to write a review a month after they’ve purchased a product.

- Cancel the reservation if nobody shows up after 15 minutes.

- Pay the user 3 days after completing the task if there are no complaints from other users.

- Cancel the order if not paid after 48 hours.

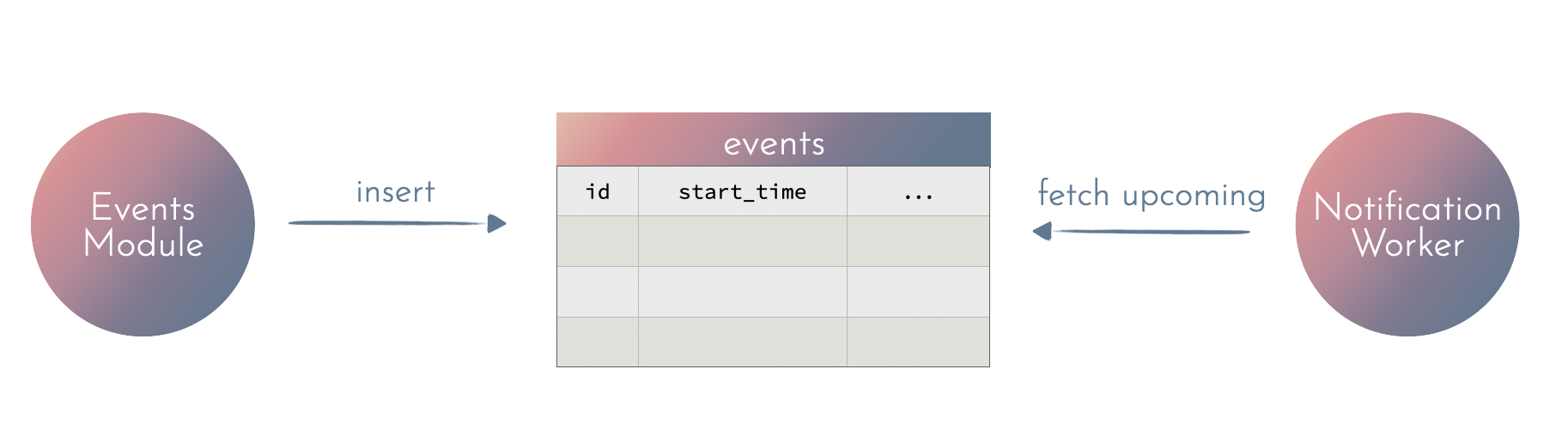

Pull-based approach

Let’s consider the simplest example: sending a reminder before an event.

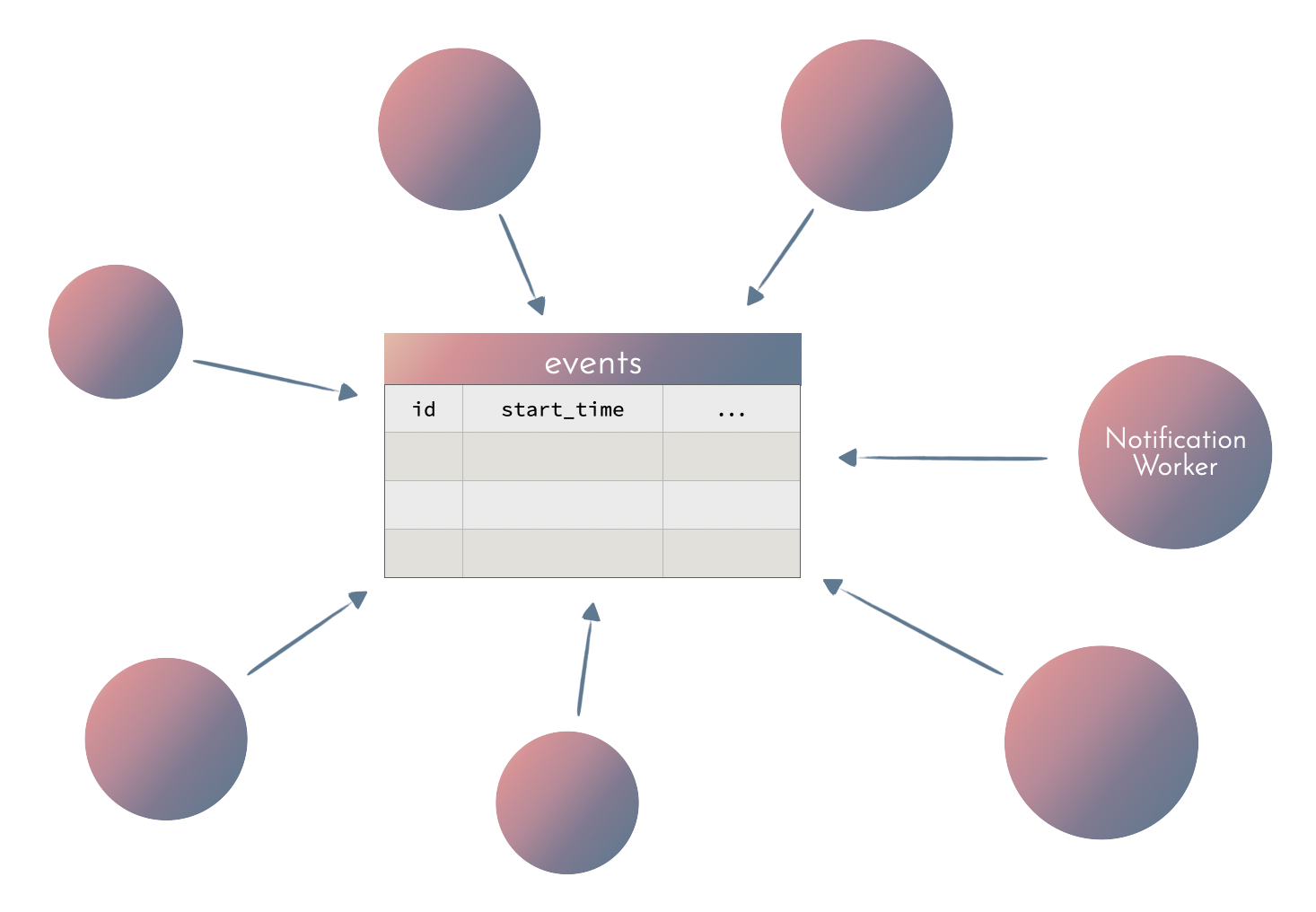

Since the notification relies on a timestamp on the events table, we can implement that feature using a periodic background job / worker that queries the table and sends the notification for events that are within a certain interval. The background job pulls the data from the main table.

# Executed by the worker every `interval` seconds

def send_notifications(interval \\ 30, now \\ DateTime.utc_now()) do

interval_start = Timex.shift(now, minutes: -(10 + interval))

interval_end = Timex.shift(now, minutes: -10)

Event

|> where([e], e.start_time >= ^interval_start and e.start_time <= ^interval_end)

|> Repo.all()

|> Enum.each(fn event -> send_notifications(event) end)

end

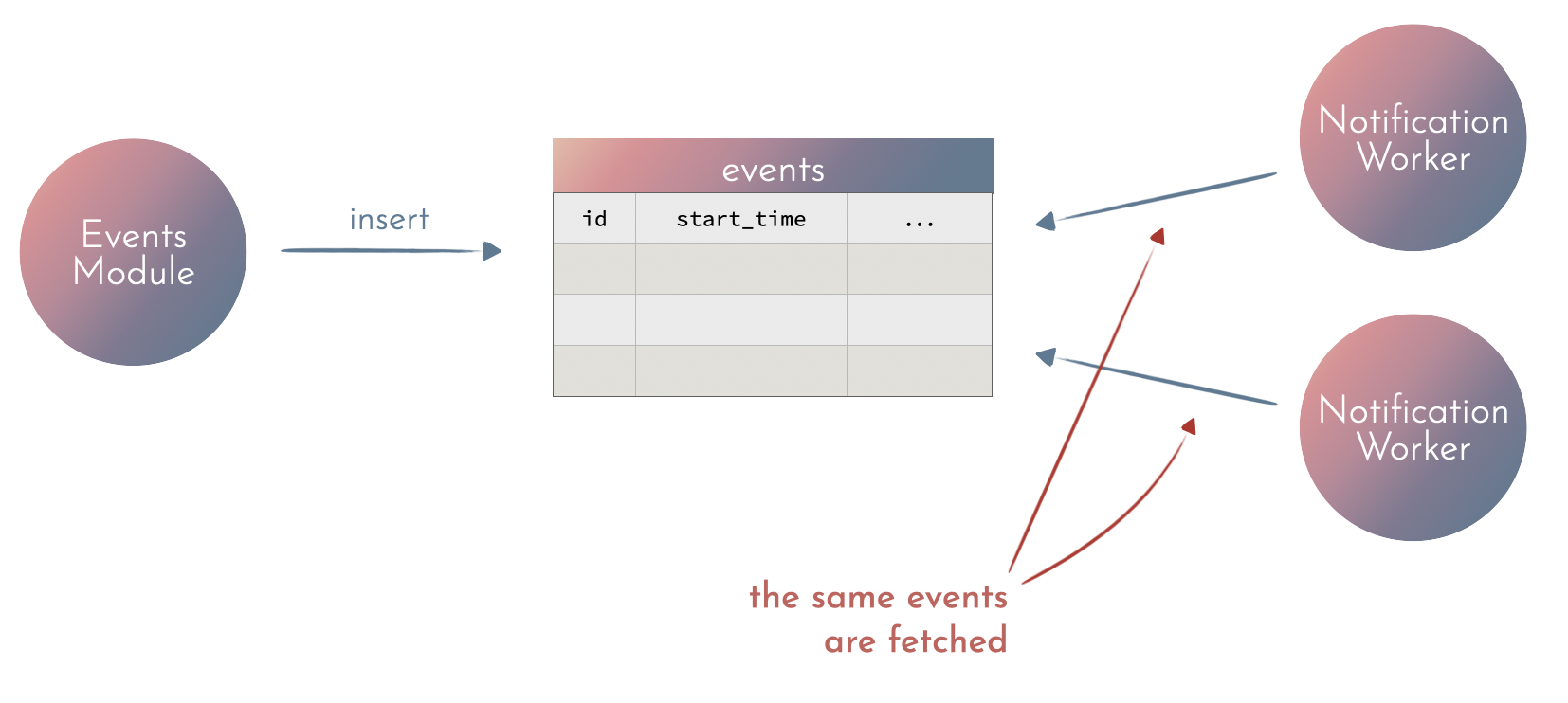

There are some problems with that approach:

- How to make sure that we don’t miss a notification when a server is down for a while?

- How do we make sure that no notification is sent more than once?

- How do we add new workers without duplicating any notifications?

There are some ways to solve the problems above. But let’s consider how we can avoid them by introducing a read model for a background job.

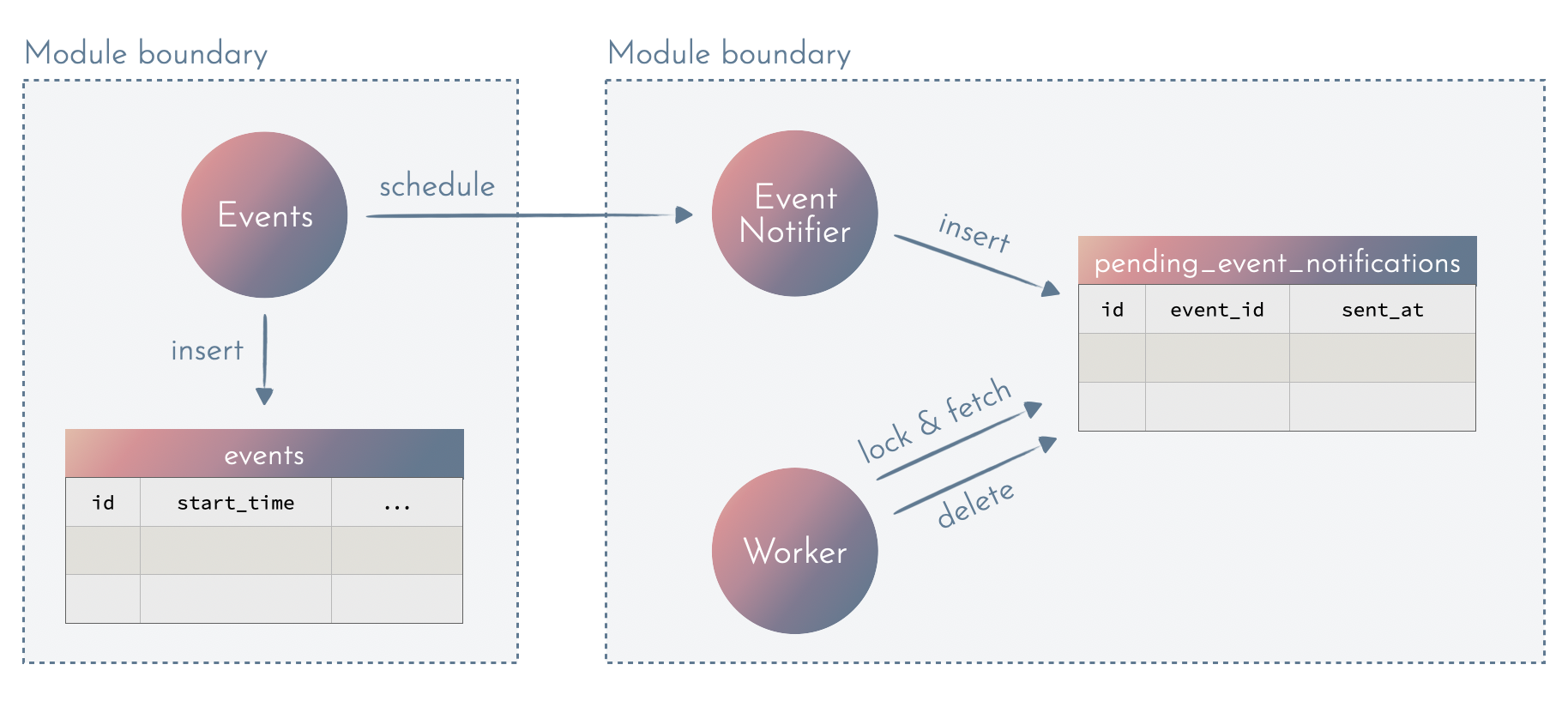

Read Models - a push-based approach

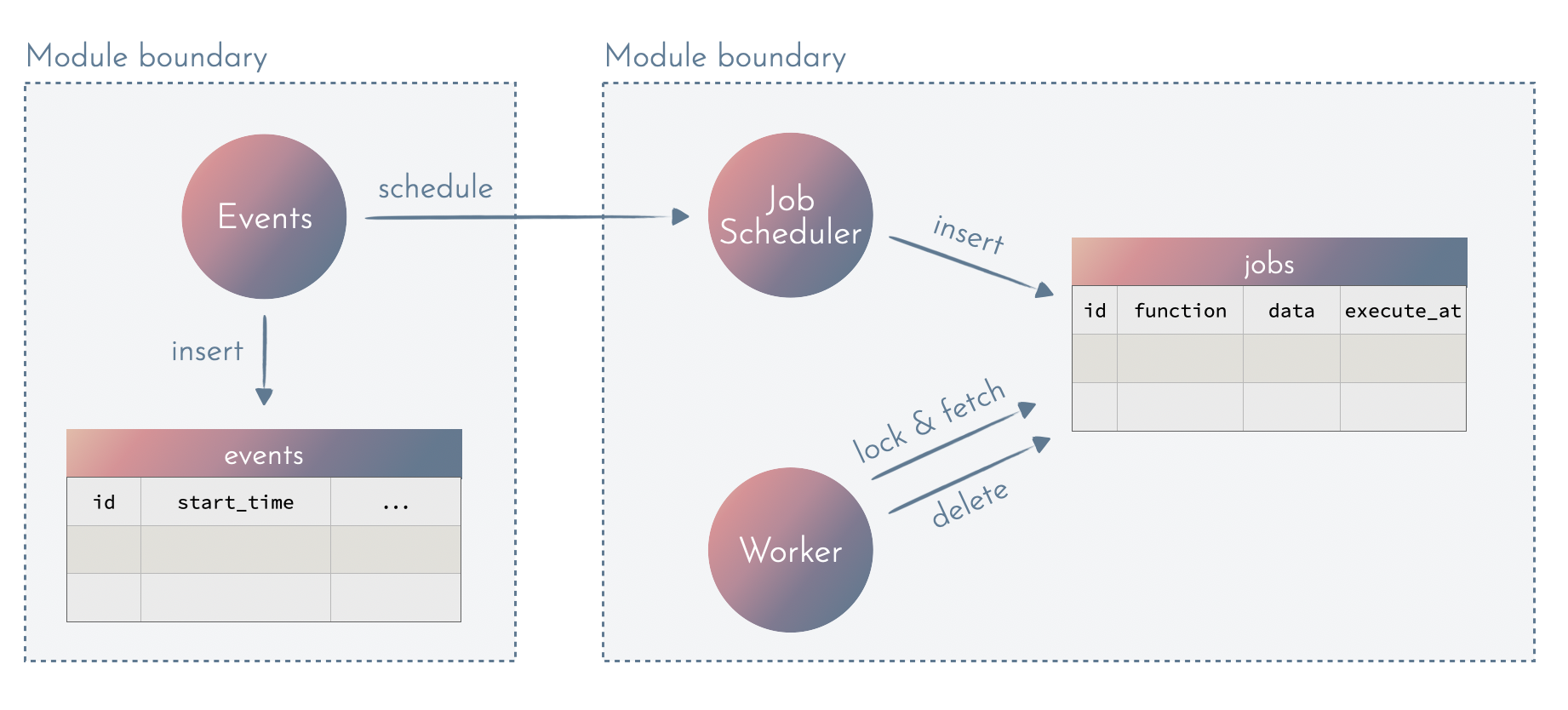

Rather the worker pulling the data, we can push the data to the module handling the notifications:

This approach relies on two things:

- Adding a dedicated read model designed specifically for notifications and used only within that module.

- Putting the behaviour behind an explicit interface - the

schedulefunction.

What are the benefits of this approach?

DB locks

The notification context owns its data. It means it can use locks to properly handle concurrency, without blocking other tables and interfering with other contexts:

def send_notifications(now \\ DateTime.utc_now()) do

threshold = Timex.shift(now, seconds: -10)

Repo.transaction(fn ->

PendingEventNotification

|> where([n], n.sent_at >= ^threshold)

|> order_by(asc: :inserted_at)

|> lock("FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED")

|> limit(@batch_size)

|> Repo.all()

|> Enum.each(fn notification ->

:ok = send_notification(notification)

Repo.delete(notification)

end)

end)

end

This approach means adding new workers won’t cause any problems. No matter if you want to increase the worker pools, or just add more application instances, the processing will be just fine.

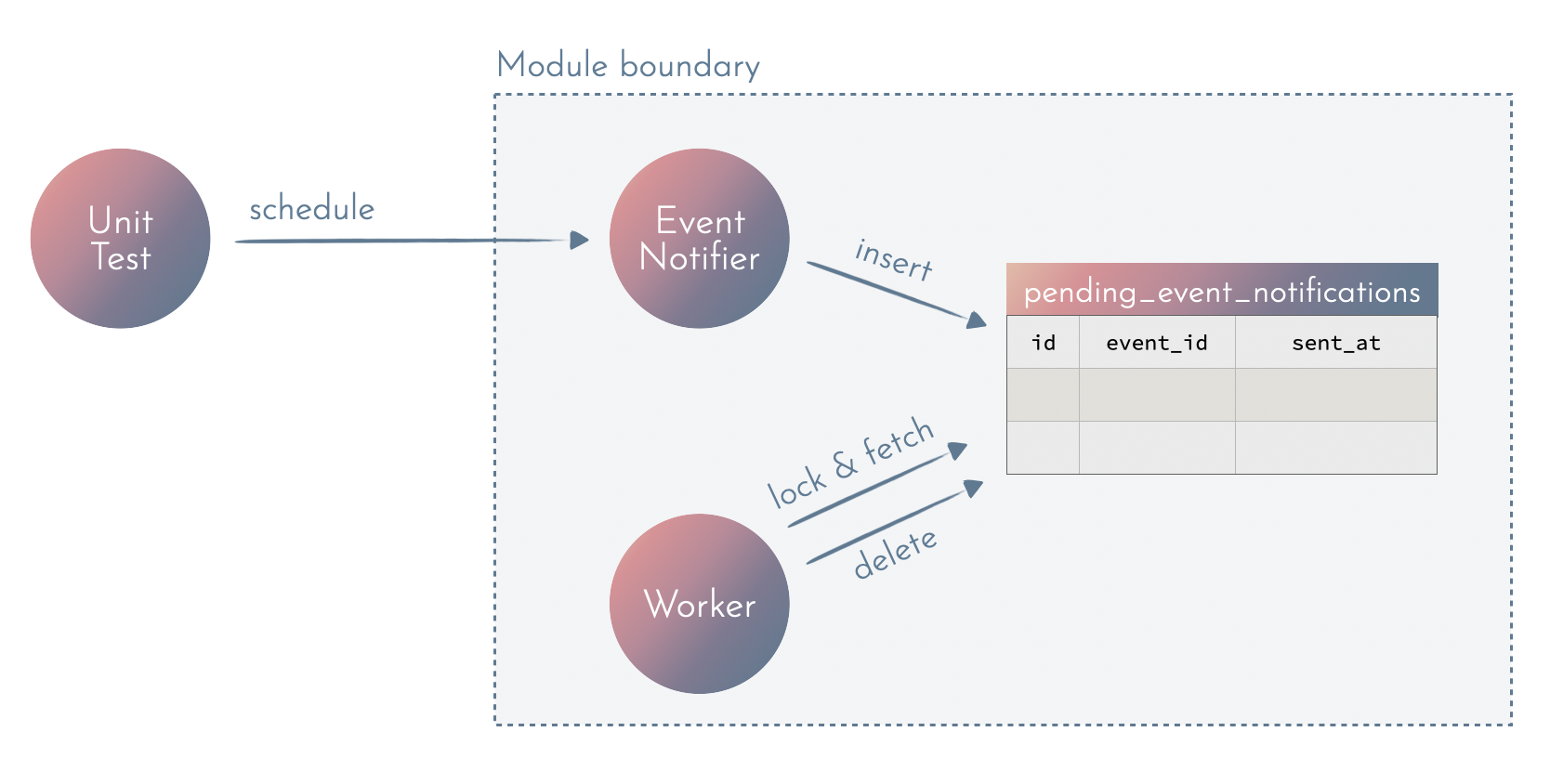

Easier unit testing

A well-isolated context is often easy to test. It’s why looking at the ease of testing is one of the things I look at when evaluating my designs.

We’ve isolated the data used for sending notifications. We’ve put a clear interface around the notifications context. This means that we can easily test that context using only that interface and avoid doing a big setup, which includes creating a lot of test data. This is both simpler to write and maintain, and make the tests run faster.

Debugging and measuring

If your application deals with managing events, the events table will grow a lot (hopefully!).

There will be more entries, the number of fields will grow with time and with new features. With more and more different contexts querying the table, the number of indexes will grow as well.

This can be a mess.

An isolated table used for one purpose only allows us to fine-tune the performance, measure the execution times precisely, limit the number of entries, and use a minimal set of DB indexes.

When notifications become slow, we know exactly where to look for the cause.

It’s not only about performance, though. By isolating a part of the system, we make that part simpler. By reducing the impact of decisions to a single module, we make it easier for us to deal with most problems.

Replaceability

One of the benefits of modular design is that we can easily replace individual modules as long as we keep the interface the same.

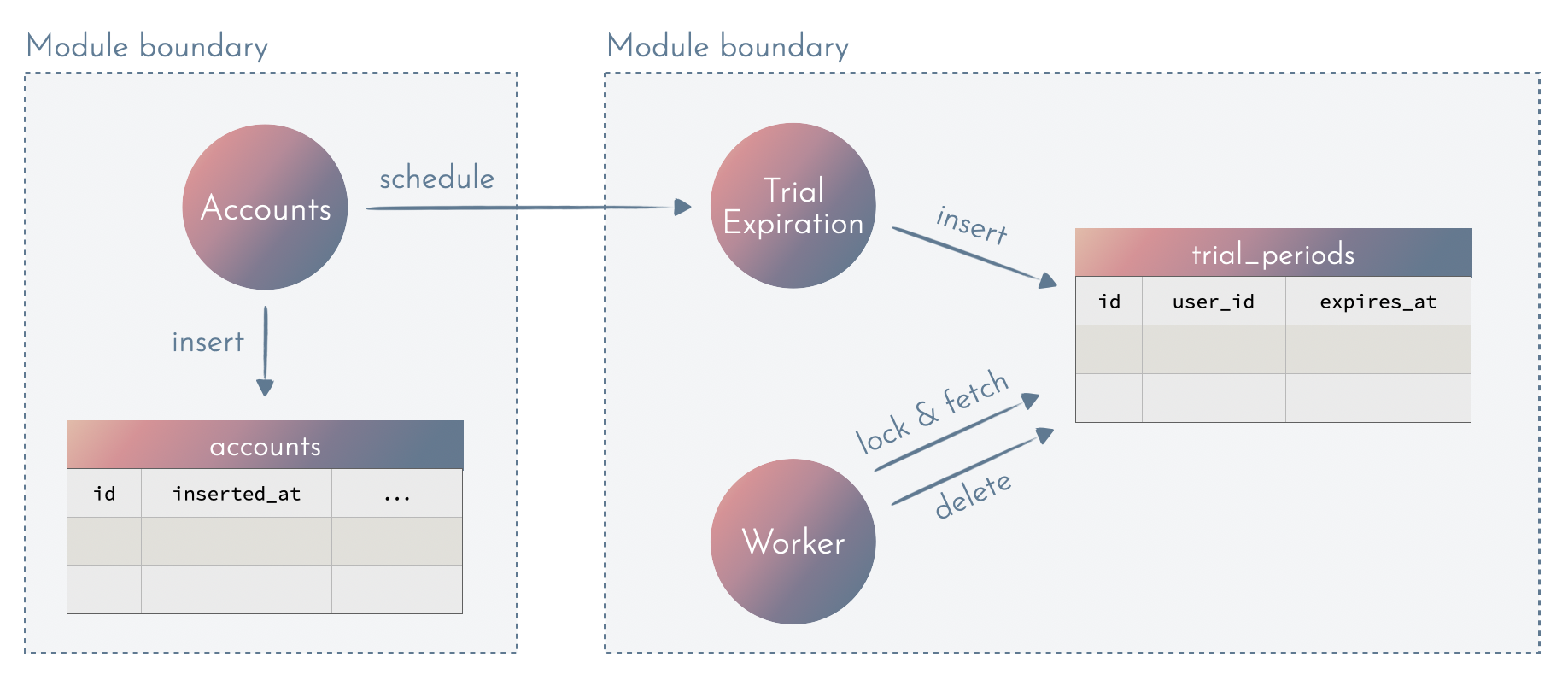

We can see the same pattern in different use cases:

We can notice that some parts are the same:

- At given time, send the notification about an event to all participants

- At given time, expire the trial period

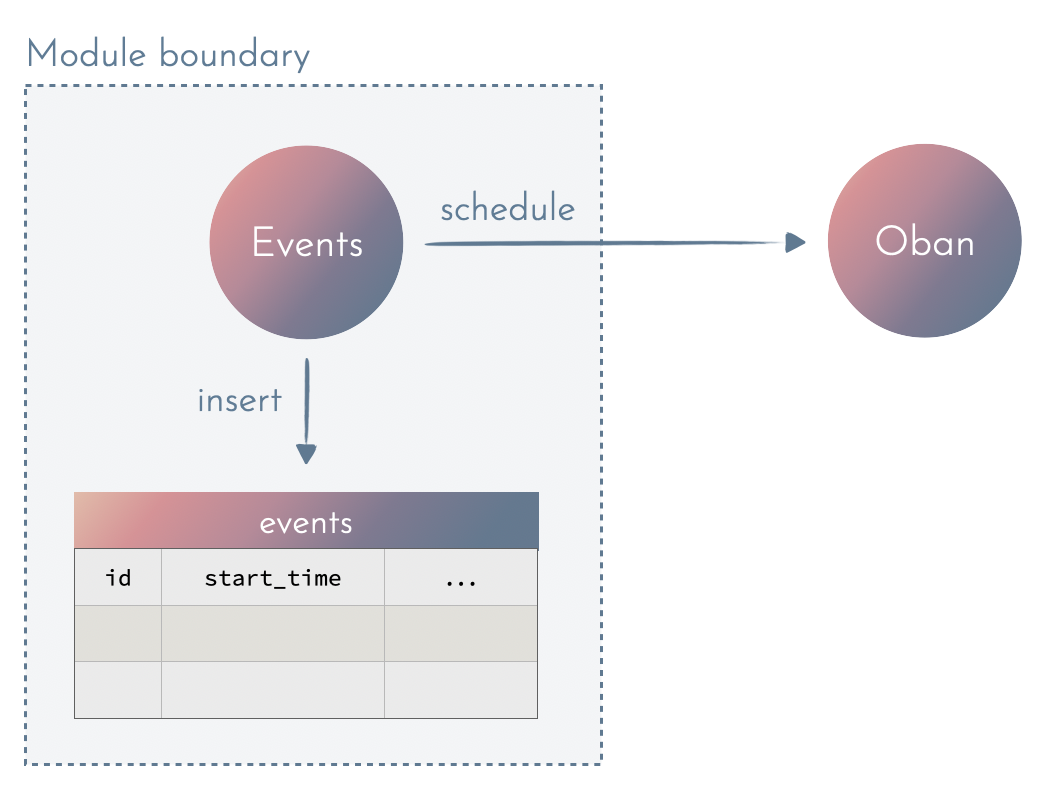

The bold part is so generic that we can easily extract it from both solutions or use existing libraries like Oban (for Elixir) or Sidekiq (for Ruby):

Since the behaviour was isolated from the beginning, doing such a change is a simple and safe task.

Extensibility

There are also some cases when a generic background job library won’t help us that much.

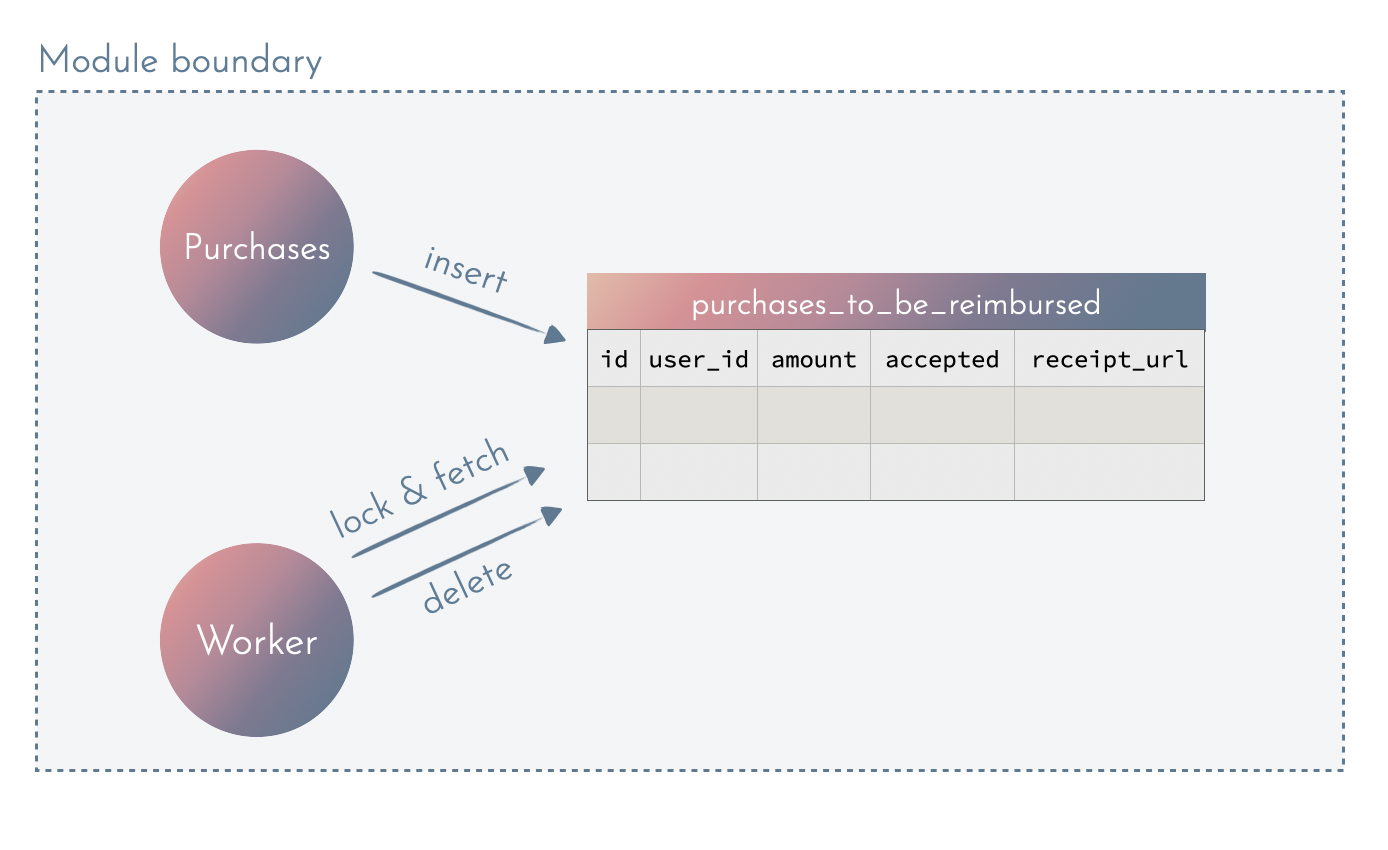

Imagine that our use case is: A user is reimbursed for a purchase after their supervisor accepts the invoice, but no sooner than 3 days after the purchase.

In such cases, having a separate context handling the use case makes it easy to extend the data model to suit the needs better.

Having an isolated data models means we can easily extend that to accommodate new requirements and gather required data from other modules (tip: using events can be great for that.)

Normalize or not?

With relational databases, it’s easy to query the data and get every piece of information we need.

As a result, the default approach seems to be to write the data once when something happens (in a normalised form) and then, when it’s needed, query and transform the data.

Denormalizing data is a useful tool in a modular design toolbox. Having clear boundaries is really hard when multiple contexts share the same data. Some denormalization and duplication can really help with that.

In this post, I showed a single technique you may use to make your code a bit more modular, but I’ll leave you with a more general question for you to consider - what are the places where a denormalized read model would help you get rid of some unwanted coupling?

References

- How to implement a concurrent queue with PostgreSQL’s FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED