Why and how to avoid 'type' fields on your domain models

Some time ago I wrote about decomposing domain models to avoid ‘state’

fields.

Today, I want to explore another technique - avoiding type fields.

I’ll use book-selling* application as an example, but I’m sure you can apply it to many different domains.

* I know that e-commerce is a common example. The reason it works is that we don’t have to waste time explaining it. I’m sure that you can easily find similar problems in many different domains. If you’d like to talk about how it applies to your domain, I’m glad to talk!

Here’s what we start with:

defmodule Bookshop.Book do

use Ecto.Schema

schema "books" do

field :name, :string

field :price_in_cents, :integer

# ...

end

end

defmodule Bookshop.CartItem do

use Ecto.Schema

schema "carts_items" do

field :user_id, :binary_id

field :quantity, :integer

belongs_to :book, Bookshop.Book

timestamps()

end

end

defmodule Bookshop do

def place_order(user_id) do

cart_items = fetch_cart_items(user_id)

:ok = create_order(user_id, cart_items)

:ok = clear_cart(user_id)

end

def pay_for_order(user_id, order_id, payment_params) do

# For simplicity & brevity we ignore all the error handling

total = total_order_price(order_id)

:ok = PaymentAdapter.pay(user_id, order_id, total, payment_params)

paid_order = mark_order_as_paid(order_id)

:ok = schedule_delivery(paid_order)

:ok = send_invoice(paid_order)

end

defp total_order_price(order_id) do

items = fetch_order(order_id).items

total_price(items)

end

defp total_price(items) do

items

|> Enum.map(& &1.book.price_in_cents * &1.quantity)

|> Enum.sum()

end

# ...

end

Behavior gets more complicated

What happens if we add ebooks to our offer? The obvious difference is that the

delivery looks different for paper and electronic books. At that point the

easiest and quickest thing to do is to add a type field to our Book schema:

defmodule Bookshop.Book do

use Ecto.Schema

schema "books" do

# ...

field :type, BookShop.EctoTypes.BookType

end

end

defmodule Bookshop do

# ...

defp schedule_delivery(paid_order) do

grouped_items = Enum.group_by(paid_order.items, & &1.product.type)

:ok = schedule_physical_delivery(paid_order.id, grouped_items.paper)

:ok = schedule_electronic_delivery(paid_order.id, grouped_items.ebook)

end

end

We have to check the type field in multiple places:

defp available?(product, quantity) do

if product.type == :ebook do

true

else

quantity >= in_stock(product.id)

end

end

Tax calculation and invoicing is another place you have to rely on the type

field on a product:

defp vat_rate(product) do

case product.type do

:ebook -> 23 # VAT for e-books was 23% in Poland for a while

:paper -> 8

end

end

Problems

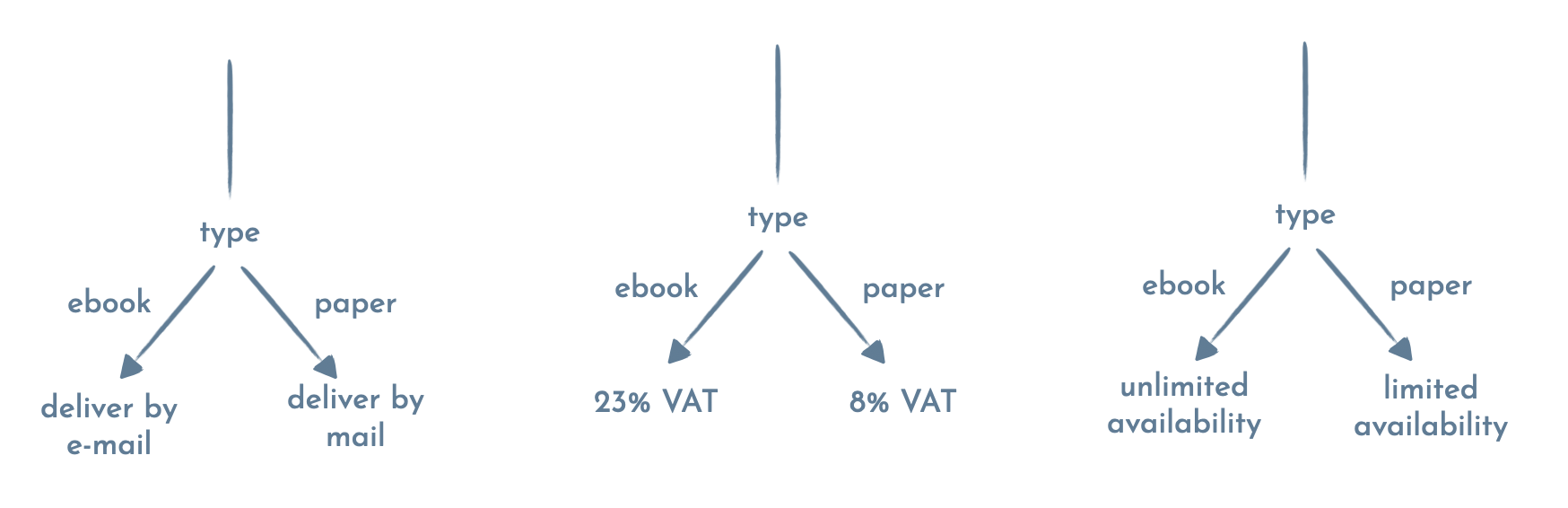

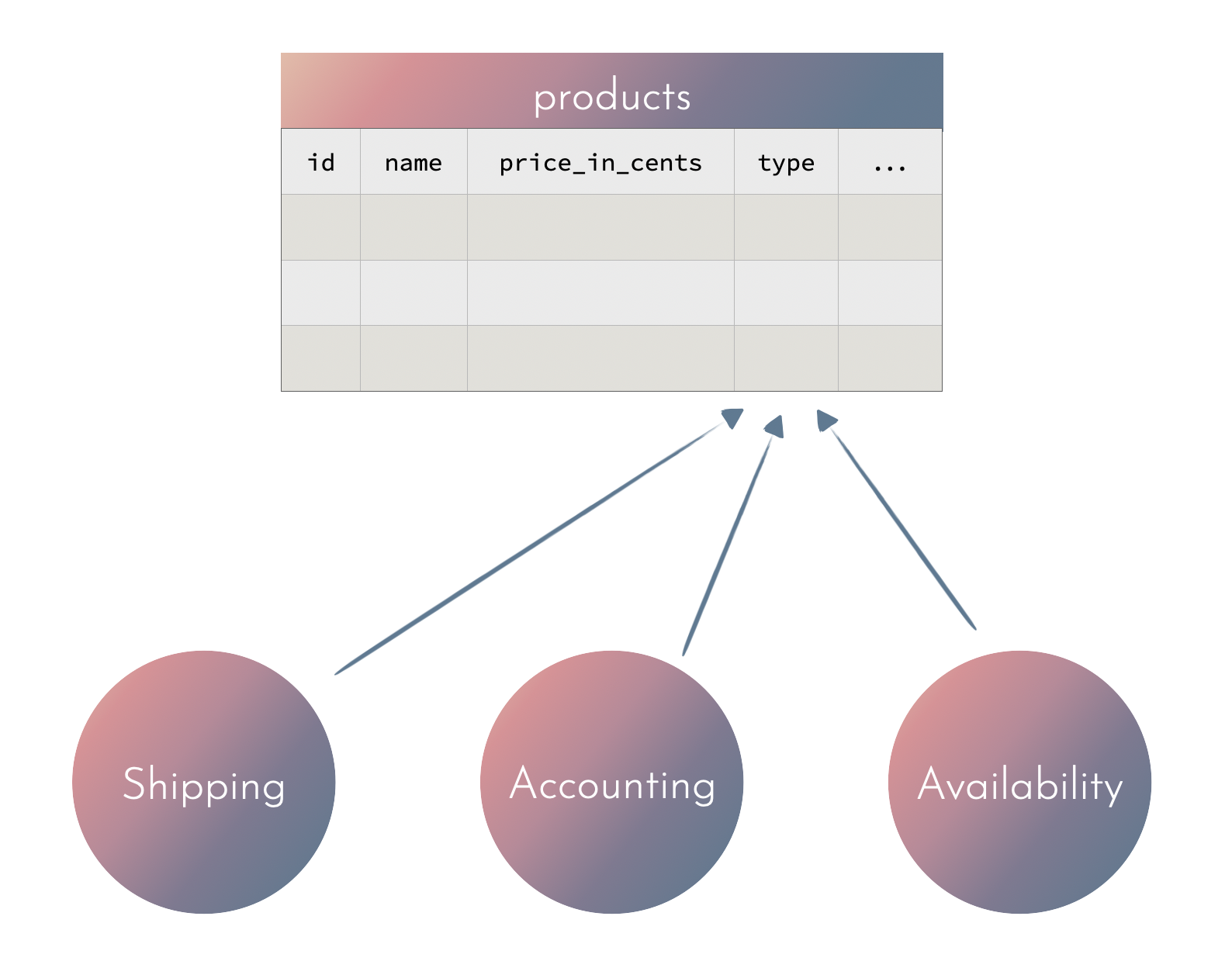

We can now see that multiple pieces of logic are tied to the same type field:

Even if we extract the code into separate modules/contexts (Shipping,

Accounting, Availability), the logic is still coupled to the same column in

a single DB schema.

Do all of those contexts change for the same reason? Of course not.

- Taxes can change (VAT for ebooks was reduced to 8% in 2019).

- The availability rules can change (example: on-demand printing).

- Shipping rules can change (example: paper + e-book bundle)

- We can add new product types.

- …

If those things will change for different reasons, our goal is to decouple those different contexts so that we can change them in isolation.

Separating models

If you see a type field, you probably have two or more entities combined

into one.

Following Domain Driven Design we can say that our type field means different

things in different contexts.

- In

Accountingphysical books and e-books fall into different tax categories. InAccountingthere’s nobundletype as well - you just pay a single tax for the paper book. - In

Shippingphysical books have to be shipped, e-books can be either downloaded or sent by email. - In

Availabilitycontexttypedoes not matter so much. The only thing that matters is whether we can sell the product or is it out of stock.

Let’s try to solve all of those different problems in isolation. How would the domain model for each context look like?

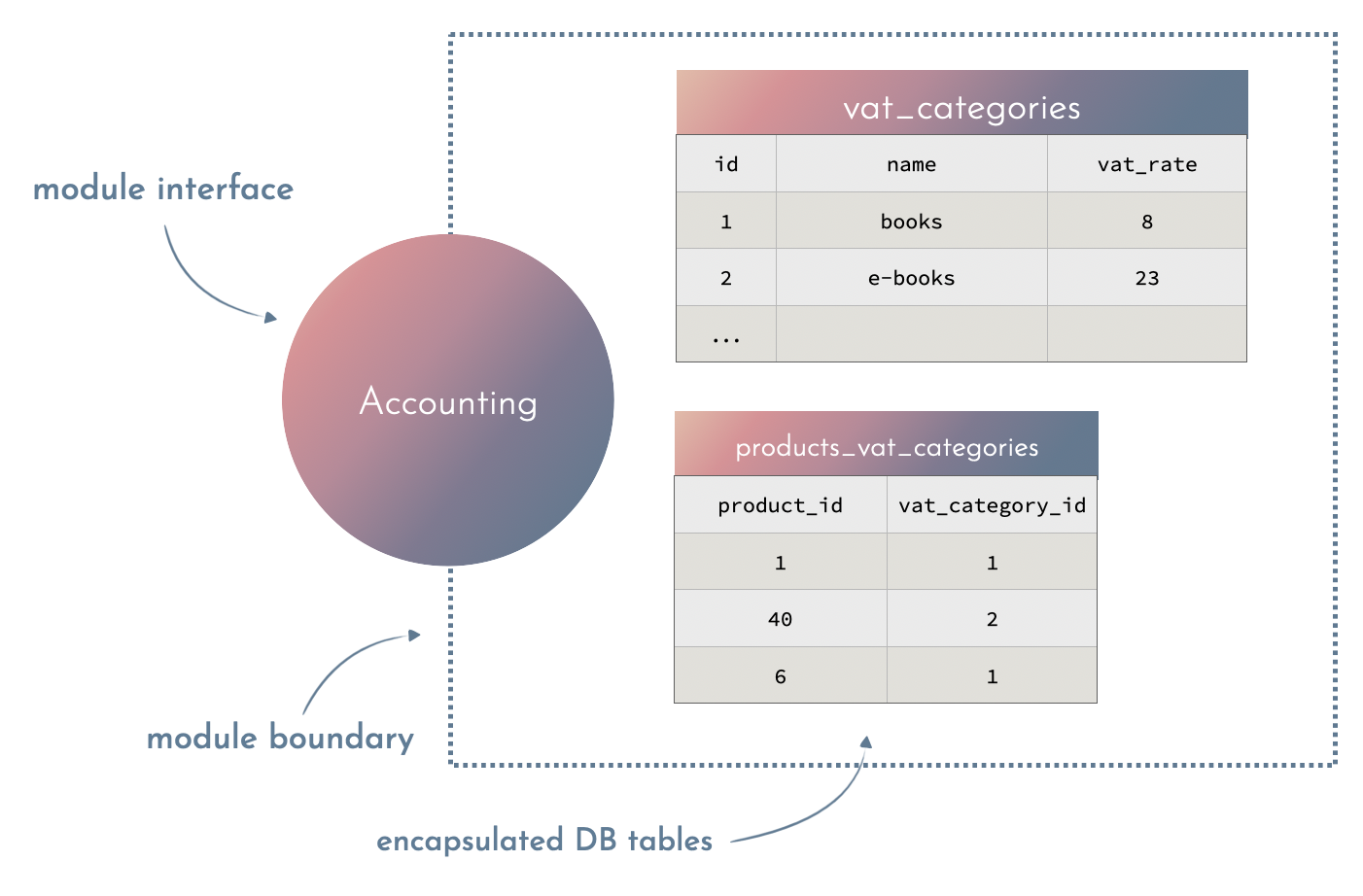

In Accounting the question we want to answer is: What is the VAT rate for this product? We can answer that question for each product by storing product_id and vat_category_id join table and another table for tax rates in each category:

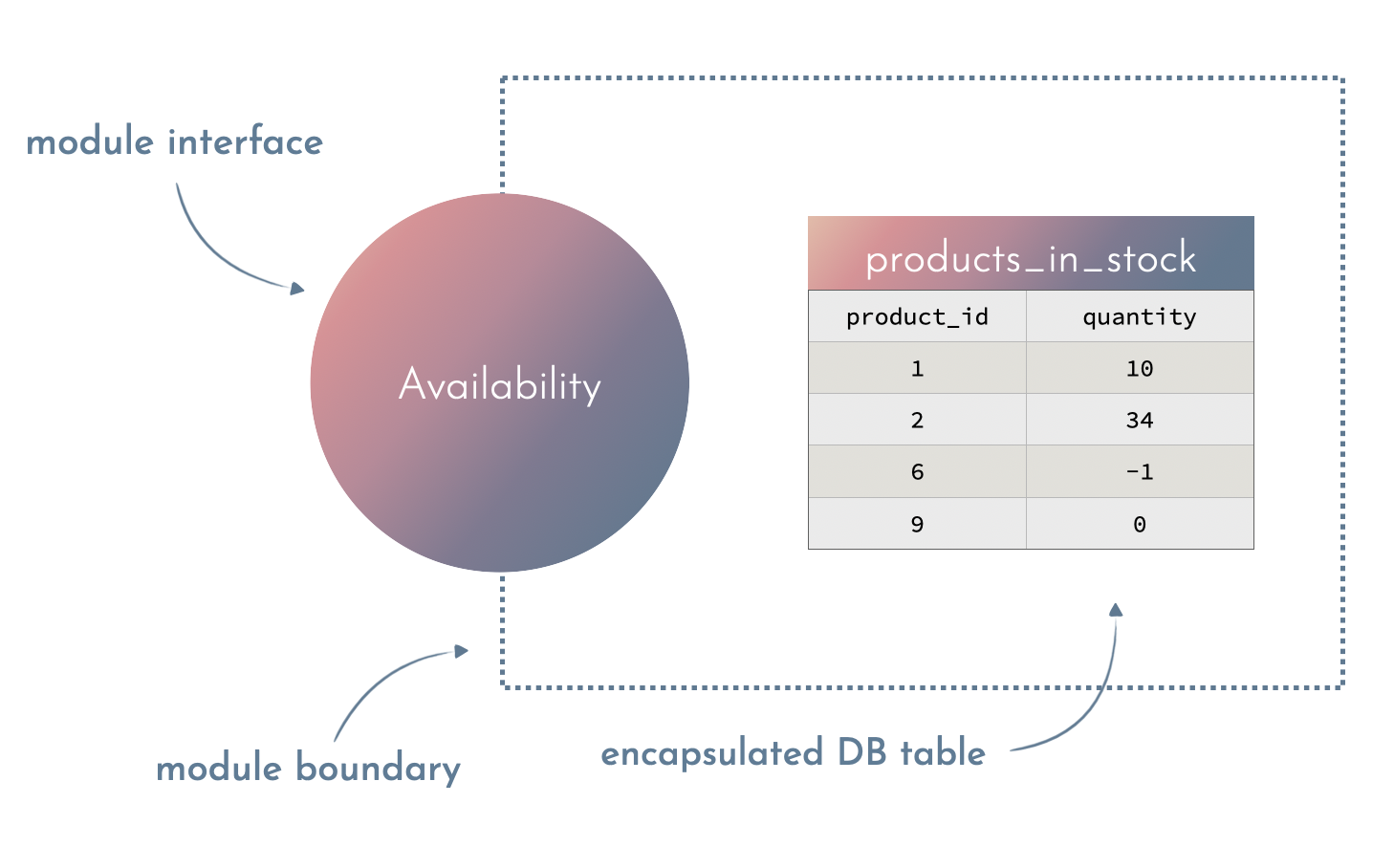

For Availability context the question is: Can we purchase X products? We can use a single table and use -1 as a sign that there’s no limit (think ebooks, or on-demand printing). Is it perfect? Of course not. But encapsulating the data model behind an interface allows us to change it easily later if we want to make it more descriptive.

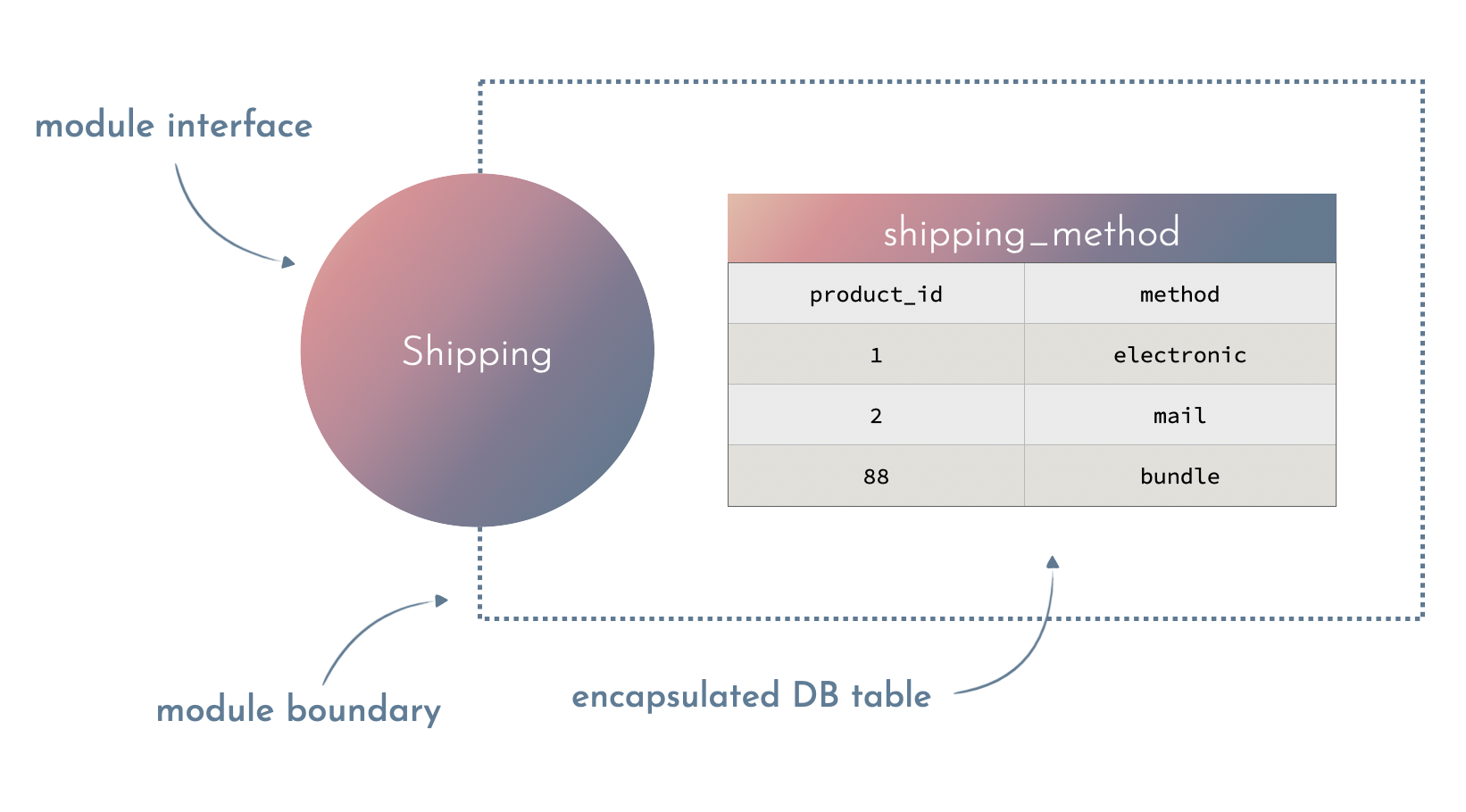

For Shipping context, a plugin architecture might work nice. We’d have different adapters for different shipment providers. Our data model only needs to know which provider to use for each product. Again - it’s not perfect. But encapsulation means that we can change it easily later.

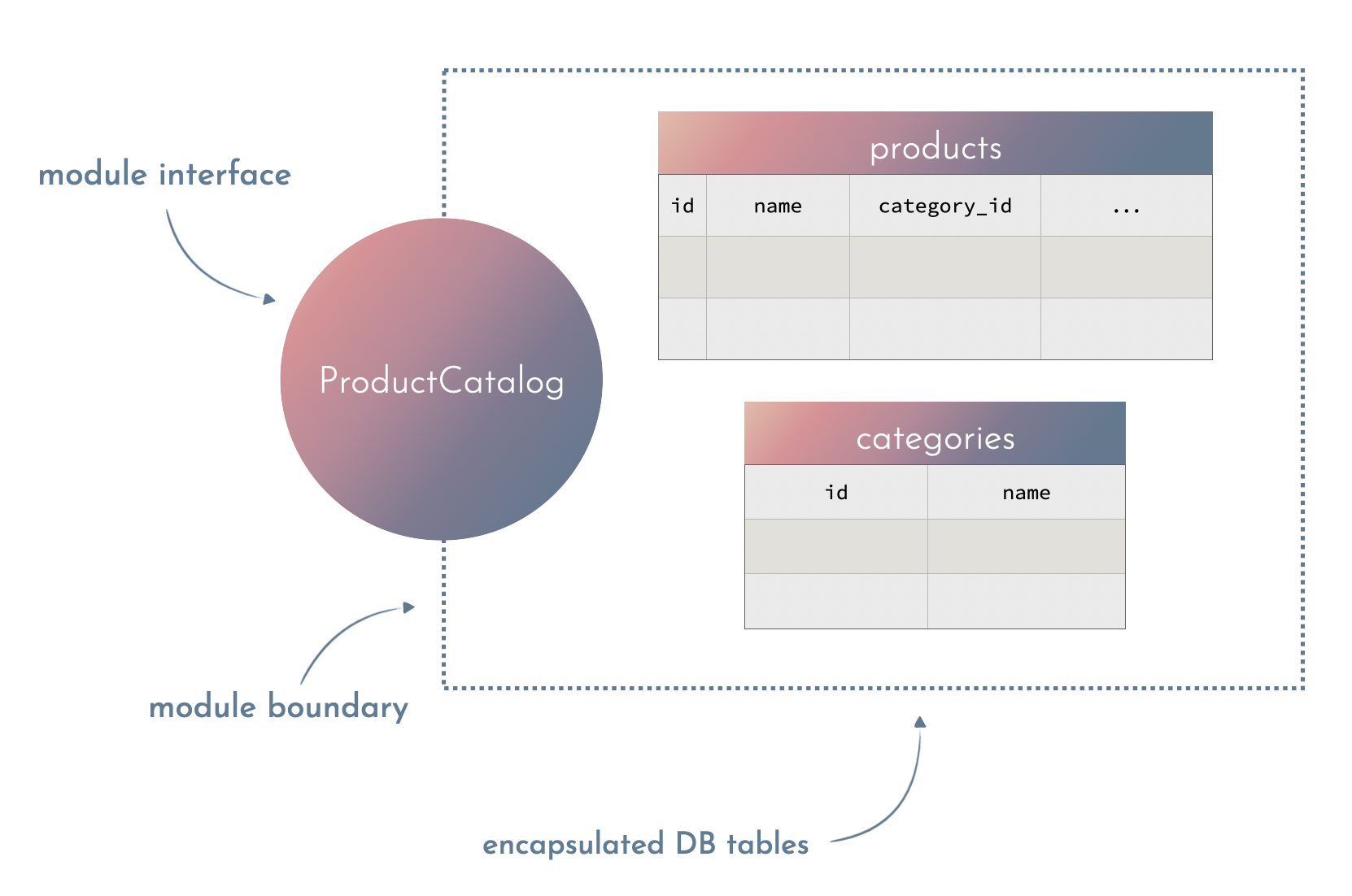

We’d also need to have a model for showing products to the customers. A type field - or a category field - in that context might be used for display/filtering purposes.

Putting it all together

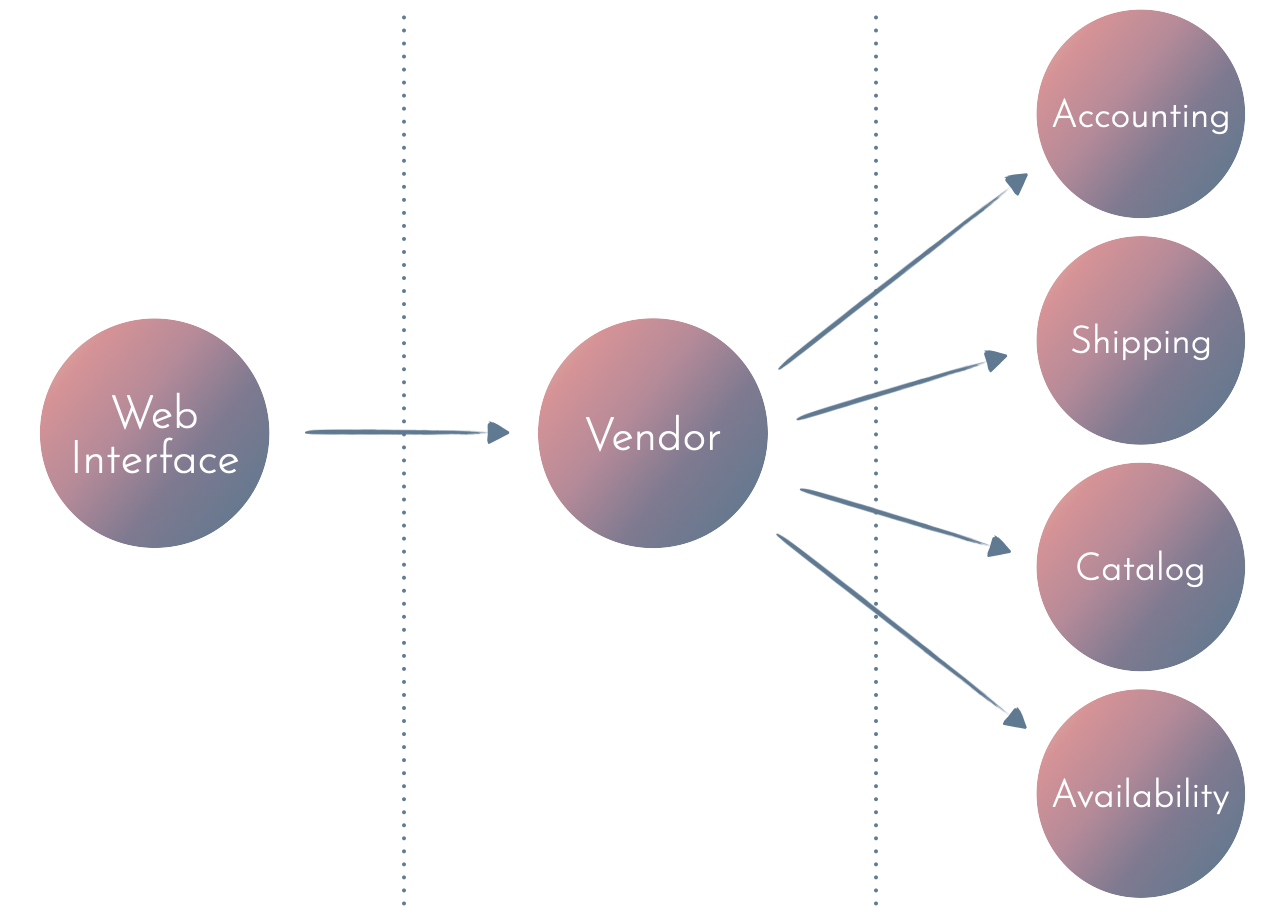

Now that we have all the pieces ready, we need to make sure that they work together. To do that, we can introduce another layer that ties the pieces together into a single use case:

def Bookstore.Vendor do

def add_product(command) do

# Error handling and transactions omitted for brevity

{:ok, product} = ProductCatalog.add_product(command)

:ok = set_availability(product, command)

:ok = set_shipping_method(product, command)

:ok = set_vat_rate(product, command)

end

defp set_availability(product, %{type: "paper", quantity: quantity}) when is_integer(quantity) do

:ok = Availability.set_quantity(product.id, quantity)

end

defp set_availability(product, %{type: "ebook") do

:ok = Availability.set_unlimited_availability(product.id)

end

defp set_shipping_method(product, command) do

case command.type do

"ebook" -> :ok = Shipping.set_electronic_delivery(product.id)

"paper" -> :ok = Shipping.set_paper_delivery(product.id)

end

end

# ...

end

We still have those conditionals, though!

We did all that work to remove the conditionals and coupling on the type field, but we end up with having to write it anyway.

How is this better?

The thing is that we cannot remove complexity. We can only move it (to be precise: we cannot remove the essential complexity, while we can remove accidental complexity).

The business process we model includes those conditionals so they have to appear in our code as well. The goal is to have those conditionals explicit and in a single place instead of being scattered around the entire codebase.

Not only is it easier to test, but resulting pieces are more reusable since the code is segregated into layers based on the rate of changes.

If we need to add new use cases (for example, paper+ebook bundle), we can just add another function in the Vendor module, while reusing most of the code from the layer below.

Story on every level

Good design tells a story. Our new design tells a cohesive story on every level instead of overwhelming you with all the details at once.

On the top level (Vendor), you can see what happens when you add a product (and you can change that easily in a single place). On lower levels, you can see all the details to understand (or change) how each piece works.

This limits the amount of information you have to process at once. You can see the big picture without being overwhelmed with the details. If you need to go deep into the implementation, you don’t need to worry about all the complexity at once.

Replaceability

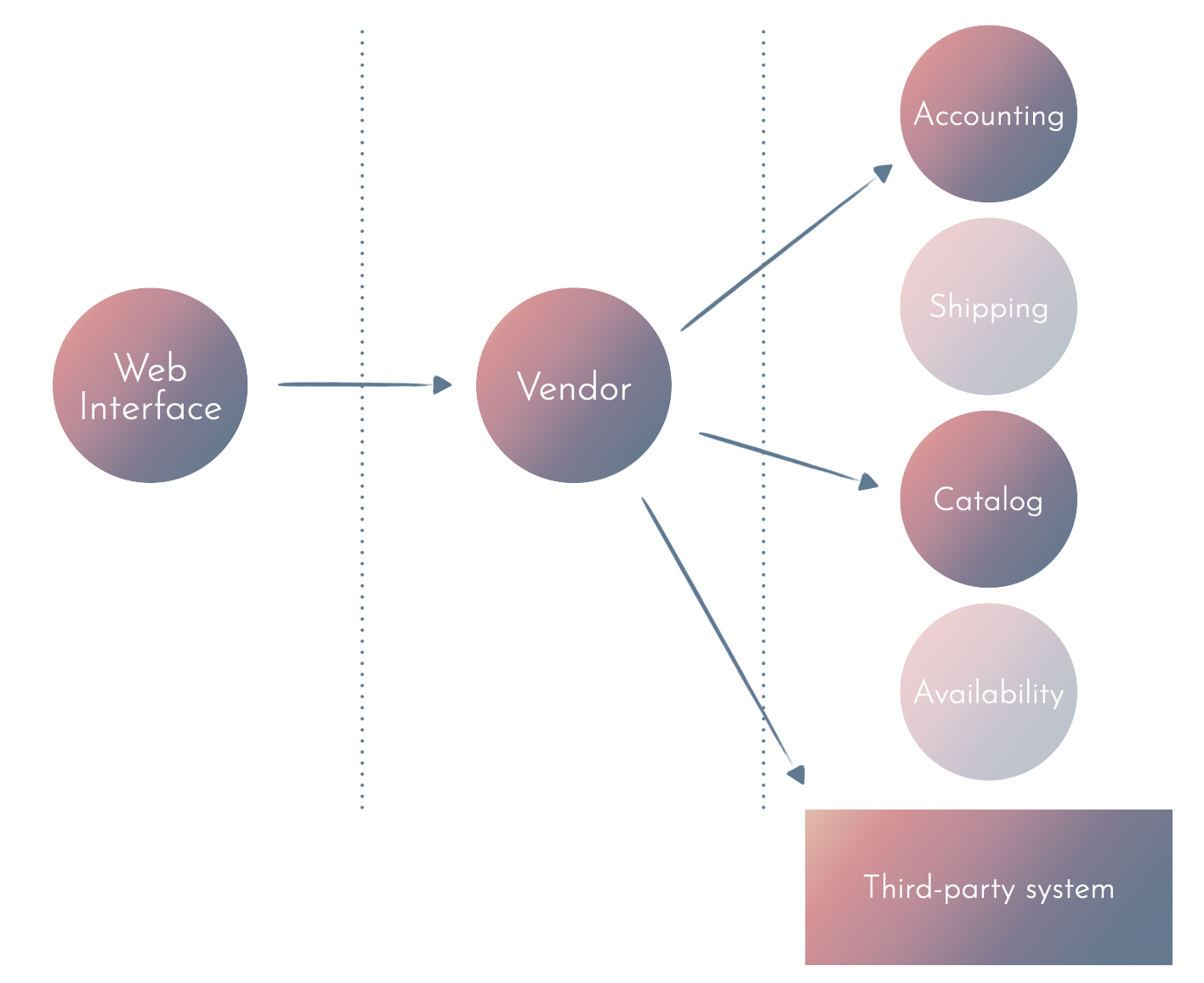

The new design allows us to easily replace each piece when necessary.

If you want to outsource all the manufacturing, warehousing, and shipping to another company, you can easily remove entire modules and replace them at the Vendor level. If we want to replace some part of the code with a third-party solution, that’s easy as well.

Remember the “composition over inheritance” rule from object oriented design? It’s a good analogy to what we did here. Relying on the type field on a domain model is similar to using inheritance to create PaperBook and EBook subclasses and has the same weaknesses. Composition (whether it’s classes or modules) gives you far better flexibility.

Refactoring

Since each piece is decoupled and encapsulates its implementation behind an interface, rewriting it from scratch might be easier than refactoring the original code.

We can also easily refactor each module and its data model in isolation. If we want to:

- change the names to tell a better story in each context,

- solve performance issues for a specific query,

- have a more fine-grained control over who can see which data (privacy/security concerns),

… it’s way easier to do if you have clear boundaries.

This article in one sentence

If you remember one thing from this article:

If you see a “type” field on your domain model, you can probably split that model into multiple contexts and use composition to make the design easier to understand and change in the future.

If you have any comments, please reach out by replying to this tweet.

References

- “The art of destroying software” by Greg Young talks about composing software from small pieces that can be easily replaced and deleted. Watching that may help you understand some of the benefits of the approach from this article.

- In “Forget Velocity, Let’s Talk Acceleration”, Jessica Kerr talks about the concepts of “Downhill Invention” and “Uphill Analysis”, explaining why it’s easier to create a piece of code than it is to understand it. Having that in mind can help you deal with the fact that good design can take longer to implement and require more code. The goal of that extra up-front work is to make understanding and changing the code easier in the future.

- Sebastian Gębski also explores the concept immutable code - that is rewriting instead of modifying the code (which I mentioned as replaceability). He goes over a few risks and conditions for this approach. Notice if you can see similarities between the prerequisites he mentions and things we accomplished in this article.

- Just Enough Software Architecture by George Fairbanks is a great book, which also uses a concept of telling a story on every level which I mentioned briefly.

- As with all things related to data encapsulation, Tell, Don’t Ask is something you should be familiar with.