Modular software design - 10 common mistakes

What’s the goal of modular software design?

Modular software design is all about dividing functionalities into independent pieces - modules. Those modules should be easy to understand, test, modify, change, replace, or delete in isolation without making a big impact on the rest of the system.

What is a module?

The word “module” can mean multiple things. In this article, I always use it in the context of modular design. A module is a piece of grouped functionality exposing an interface, by which other modules can communicate with it. You can also see it described as a component or a (bounded) context in other sources.

Do you need it?

The mistakes listed here are not hard rules. Each design decision you make should be driven by the functional and non-functional requirements.

A bicycle may be your default way of moving around. And while it’s a perfect choice for you moving around town, it would be a mistake to take in on a highway.

Context is everything. For every rule, for every pattern, always ask: How does this fit my context?

The benefits of modular design might not be a priority for you. But if they are, here are 10 common mistakes you may want to think about.

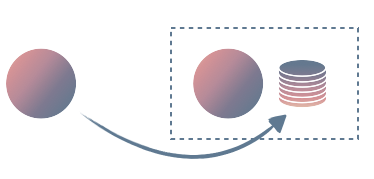

1. Using database tables from other modules

Writing and reading directly from the DB tables owned by other modules makes those modules harder to change (see also: Integration Database).

Shared DB tables often end up too complicated because they try to serve the needs of multiple modules. Paraphrasing SRP, we can say that each DB table should have exactly one reason to change. When we share a table between multiple modules, we violate that.

To avoid that, each module should own its storage and properly encapsulate it. A single table used by multiple modules should probably be split into a few separate tables, each suited for a specific need.

2. Requiring strong consistency, using DB transactions across modules

It’s tempting to use DB transactions to ensure data consistency between different modules. But transactions come at a cost.

First of all, they force you to use a single database. If you ever need to change a storage method used in some module, this is a big challenge.

Secondly, it can negatively affect the user experience, since transactions affect how the system fails. Many actions from the user require us to synchronize multiple modules. But that shouldn’t affect the end-user. A classic example - would you like to prevent the user from placing an order only because of a temporary bug in a module responsible for the delivery?All-or-nothing behaviour is not always desirable.

Transactions are often a sign of too much coupling between modules. So use transactions carefully. Using transactions should be a conscious decision made after evaluating different options.

3. Always using foreign key constraints across modules

Foreign key constraints seem to have no downside. Inconsistent data is a big problem, so who’d like to risk it?

Foreign key constraints create a really strong coupling between two parts of the system. Sometimes it’s a must-have. But it also hurts our ability to replace components as the system evolves.

Foreign key constraints also suffer from similar issues as DB transactions. Once requirements force you to drop them, you’ll need to put a lot of effort to deal with that.

Is it more important to always maintain data integrity, or to be elastic? The answer can be different for every system and every piece of data in a single system.

Look at the rate of changes, the risk and the consequences of inconsistent data, and business context. Integrity between transactions and accounts is a must-have. Integrity between a user and the list of recently-used emojis? Probably not.

4. Not testing in isolation

Testing (especially TDD) is one of the best and fastest ways to get feedback about your design.

A well-designed interface allows you to use the module easily. Low coupling allows you to skip big setup blocks before your tests. Good encapsulation means that you don’t need to test the internal state and modify the tests with each refactor. With good boundaries between the domain and infrastructure code, you don’t need to use mocking so much.

Good modular code should make each module easy to test. If you cannot easily test your module in isolation, this probably means that the boundaries could be improved. And if you don’t try to test in isolation, you miss that important feedback from your tests.

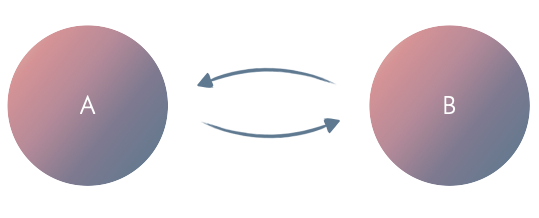

5. Circular dependencies between modules

If module A knows about module B and module B knows about module A, it’s a clear sign of troubles. Either the modules are too coupled (maybe they should be merged into one module?), or there’s a third module waiting to be extracted.

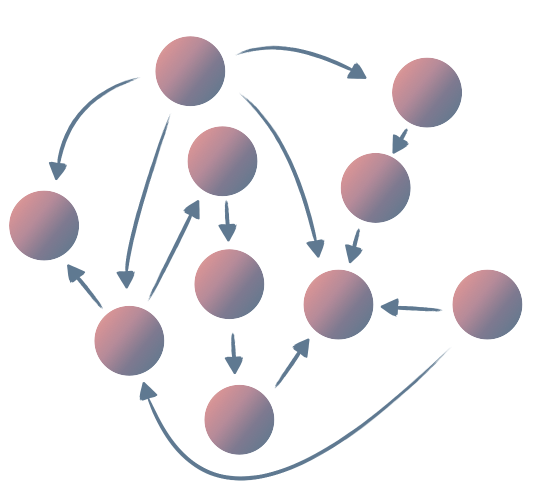

6. Too small modules

When we start fighting with a big ball of mud, we overcompensate. We want to run away from big modules and we end up with modules that are way too small.

It’s not the size of a module that matters, though. It’s the complexity and coupling. Most problems come from either:

- modules doing too much to understand them easily (too complex)

- modules that don’t do anything interesting on their own and need to collaborate with other modules extensively to accomplish something (too much coupling),

Instead of worrying about size, think about coupling, coherency and good encapsulation.

7. “Dumb”, entity-based modules & poor encapsulation

The job of our software is to do something. If you organize your modules around the entities, you will probably need to synchronize multiple of them to accomplish any business action.

The easiest way to avoid this is to think about the behavior of the module. What does it do? Once you know the behavior, only then think about the necessary data. Then make sure that the data is encapsulated behind a clean and deep interface.

Following Tell, Don’t Ask principle can also help you to avoid this problem.

8. 1-1 correspondence between controller actions and business functions

Putting business logic in the web controller is a common issue. So one of the first changes we do is to move all the code out of the controllers.

Controllers should not just be a pass-through layer, though. They shouldn’t contain business logic, but it doesn’t mean that there should not be any code in them.

Controllers (and the web layer in general) have a role - they communicate between the domain layer and the rest of the world.

There’s nothing wrong with calling 2 or more functions in the web controller if you need to pre-process the parameters or fetch more data to render. There’s nothing wrong with doing two query calls instead of using a join. Application-level joins have a bad reputation, but they can be a useful tool for achieving better modularity (especially when gradually refactoring an old codebase).

Changing the response format shouldn’t affect the domain code (and its tests) just as changing the way you store data shouldn’t affect the web layer. Doing the translation from the domain concept to the web concepts (and vice versa) at the controller level creates a boundary that ensures that you can modify each of the layers in isolation.

9. Too much code reuse

Sooner or later, we’ll need the same functionality or piece of code in two or more modules. It’s tempting to extract that code into a separate module. But doing that for the wrong reasons can introduce unnecessary coupling and make changes harder.

The question to ask yourself: will the duplicated parts always change at the same time? If the answer is yes, code reuse might be a good idea. But if the code is only the same at the current time, there’s nothing wrong with using the same code in two places. DRY was never about mechanical code duplication, so don’t be afraid of the good old copy-paste sometime.

For a more in-depth exploration of code reuse consequences, check out this article by Jessica Kerr.

10. Not watching the domain boundaries and language

Modular design is all about being able to make changes in software easily, within a well-defined boundary. But if the boundaries of the modules you create are misaligned with the natural boundaries of your problem domain, making changes can still be hard.

Strategic Domain Driven Design is a great way to prevent that. No amount of technical patterns, architecture choice, or refactoring can replace good domain knowledge.

Learning about the domain can bring you more benefits than reading another architecture book. It’s been said that naming is one of the hardest problems in computer science. Did you wonder why?

Language is extremely powerful. The way you name a thing influences the way people think about it.

Talking to the domain experts will help find that good naming. It will also help you find the natural boundaries of the business domain you’re working with.

If you follow the language and those natural boundaries, the code will easily fall in the right places. The changes you make will likely fit inside those boundaries as well, which is the ultimate goal of modular software design.

Extra: Trying to find a “correct” solution.

Software design is more art than an exact science. There are multiple good ways to structure your system and draw the boundaries. And what works well will change with time, requirements, scale and many different factors.

So don’t overthink it. Don’t look for the perfect solution. Don’t be paralyzed by the number of architectural patterns and the number of options. Learning theory is great, but nothing beats practice.

Start small, try different things, incrementally make the changes to the real system, observe how it affects you and your team and iterate.

Optimize for evolvability. If you cannot decide which option to choose, go with the one that allows you to change your mind later. Best decisions are the ones you can easily reverse later.

References:

- On the Criteria To Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules is probably one of the first academic papers about Modular Software Design. It’s almost 50 years old (!), but still highly relevant.

- Michael Nygard wrote a great post about the Entity Service Antipattern

- A Philosophy of Software Design by John Ousterhout is the source of the concept of deep vs shallow interfaces and a collection of many other easy-to-follow design heuristics. Highly recommended.

- If you need some inspiration and a specific modelling technique, check out my post: Decomposing domain models based on lifecycle

If you have any comments, please respond to this tweet.