A guide to event handling in Elixir

Using events is a common way of integrating different parts of a modular system. But while the concept is easy to grasp, the implementation can be tricker.

Integrating subsystems is hard, and there are always trade-offs. Events are not different.

There are many possible ways of event handling. Choosing the wrong one for your needs can be a serious mistake.

This article shows you some of the choices available and trade-offs you have to consider with each of them. Some are related to Elixir itself, and some are technology-agnostic.

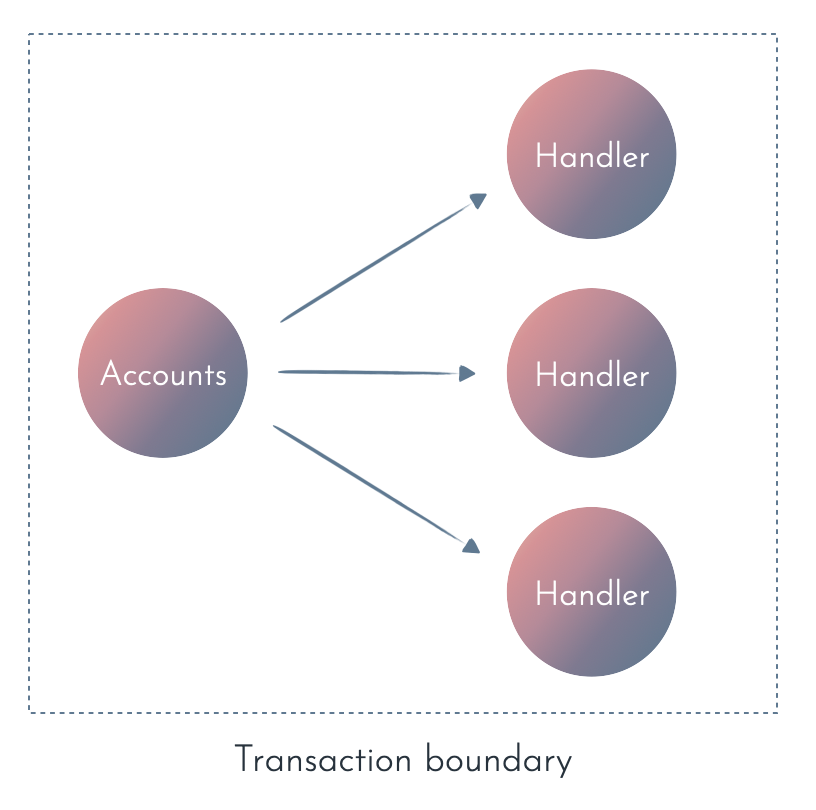

1. Synchronous processing

The simplest way to process events is to do this synchronously:

defmodule Accounts do

def sign_up(params, event_handlers \\ [Mailer, Notifications]) do

# You can wrap the entire function in a transaction

# to ensure strong consistency.

user = save_user(params)

event = %UserSignedUp{

user_id: user.id,

name: user.name,

email: user.email

}

for event_handler <- event_handlers do

event_handler.handle_event(event)

end

{:ok, user}

end

end

Synchronous processing has multiple benefits and it should probably be the first step (especially for existing applications) unless you need the benefits of asynchronous processing.

If you’re running a modular monolith with a single database, you can even use a database transaction to guarantee strong consistency between the data and the event.

That way, you can start decoupling your contexts logically (see: Events and different kinds of coupling) without dealing with the technical challenges of asynchronous code and eventual consistency.

The trade-off is that synchronous processing and/or a transaction means all or nothing semantics. Either everything works correctly, or nothing is saved.

All or nothing makes the code more predictable and easier to debug, but it’s not always desirable. When it’s an issue? When the customer places an order, you probably want that information saved even if there’s a temporary bug in the code handling that shipping.

When to consider synchronous event processing?

- When you have little experience with events.

- If you don’t want to introduce additional technical complexity and infrastructure costs.

- In a monolith system, which you’d like to make more modular.

- As a replacement for other mechanisms in the test environment.

When is synchronous processing not a good idea?

- When you need to isolate failures.

- When quick response is crucial (and you know what you’re doing).

- For long-running, asynchronous, or third-party side effects. If side effects are out of your control, it might be a better idea to handle them in a proper asynchronous fashion.

- When side-effects can be delayed or batched in the background for better performance.

- When you’re communicating across different services (in other words - in a distributed system).

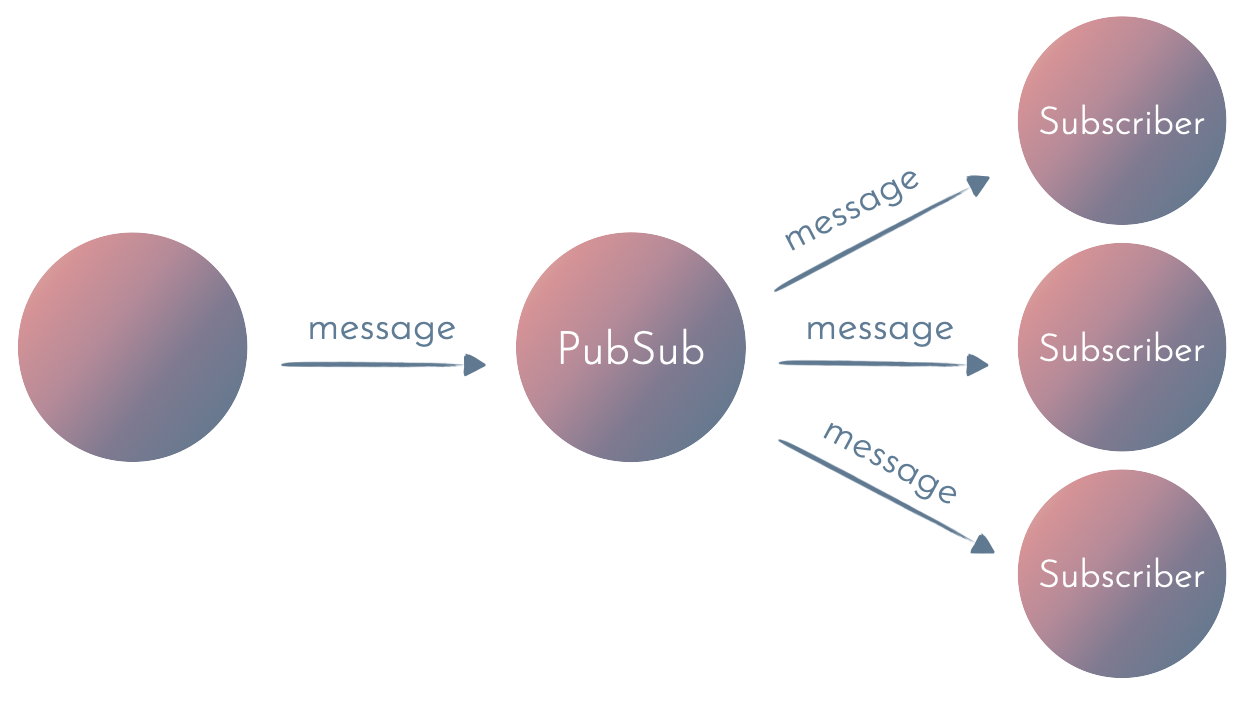

2. Process-based PubSub

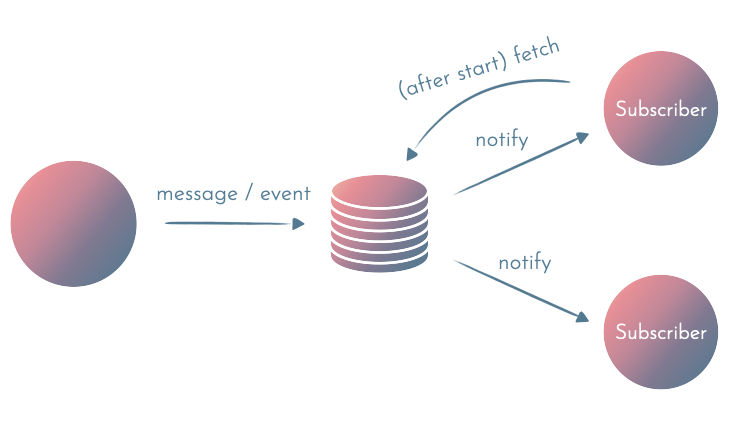

Since processes and message passing are basic building blocks in Elixir, we can use an in-memory PubSub mechanism (for example Registry or Phoenix PubSub for a single node) to broadcast events to subscribers.

defmodule Subscriber do

use GenServer

def start_link() do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, name: __MODULE__)

end

def init([]) do

PubSub.subscribe("user_sign_ups", self())

{:ok, %{}}

end

def handle_info(%UserSignedUp{} = event, state) do

:ok = Mailer.send_welcome_email(event)

{:noreply, state}

end

end

Such in-memory PubSub offers at-most-once delivery semantics. That means that the message will either be received once or won’t be delivered at all.

At-most-once delivery means that if we handle side effects or events using an in-memory PubSub mechanism, the side effects are not guaranteed to be executed:

- If a subscriber exits before the message is received, it won’t receive the message again.

- If a subscriber crashes when processing the side effect, it won’t try to process it again after restarting.

This approach should only be used if losing some messages is OK. Some common examples are:

- In-app notifications.

- Transient application state (e.g. cache).

- Things that can be corrected by next messages or a periodic job.

Be careful when sending in-memory messages from within a DB transaction:

1) The transaction can be rolled back after a message has been sent.

2) It can lead to hard-to-debug errors when a subscriber receives the message and tries to read the data before a transaction has been committed.

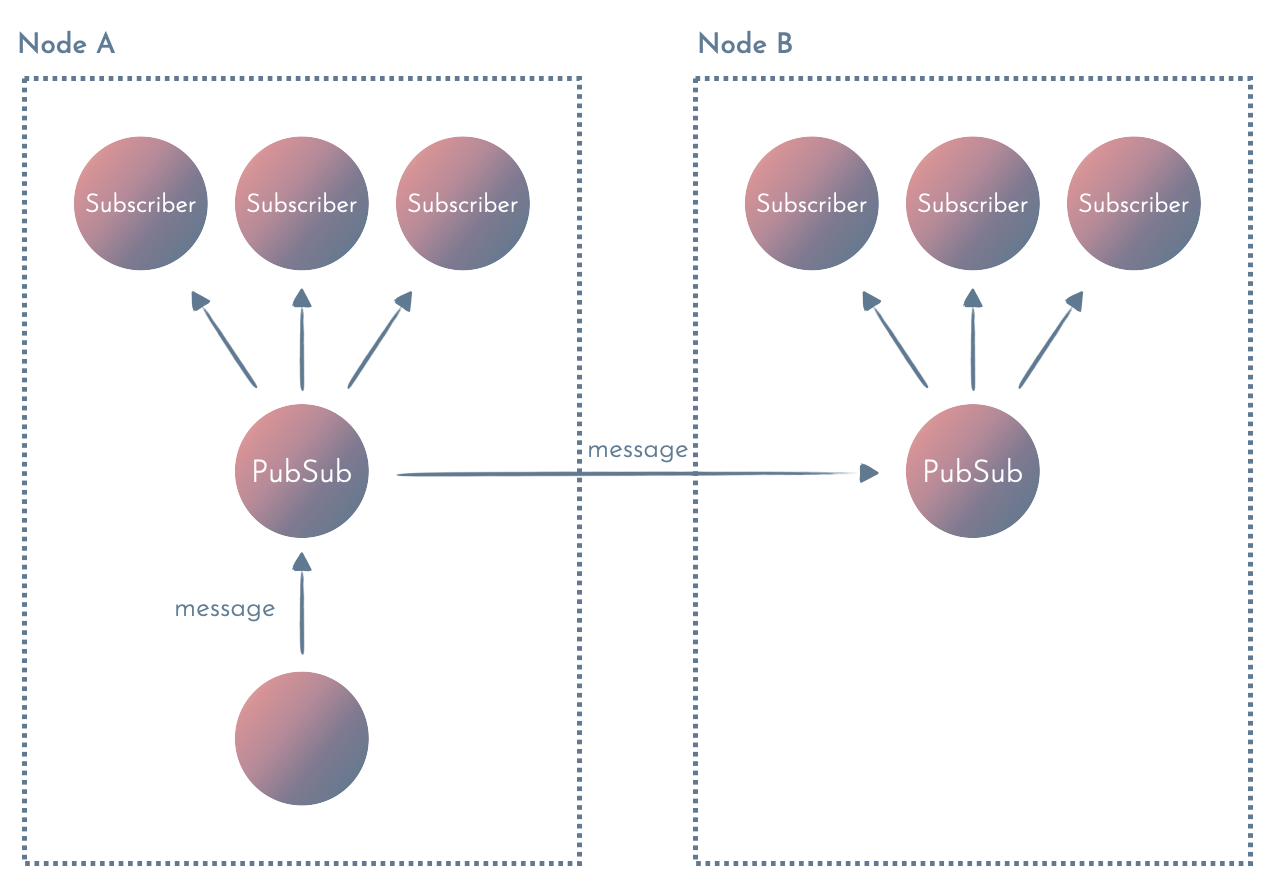

3. Multi-node, process-based PubSub

Multi-node PubSub (like Phoenix PubSub) allows you to broadcast messages to subscribers on multiple nodes.

Multi-node PubSub is usually useful for stateful processing when:

- You need to synchronize state across multiple nodes (e.g. distributed cache).

- You have clients with long-running connections (WebSocket, long-poll, …) - that’s why Phoenix Channels and LiveView use a multi-node Phoenix.PubSub).

As with a single-node PubSub, message delivery is not guaranteed. Use this solution only if losing some messages is fine

With multi-node PubSub, you have to remember to make sure that the nodes are connected to form a cluster.

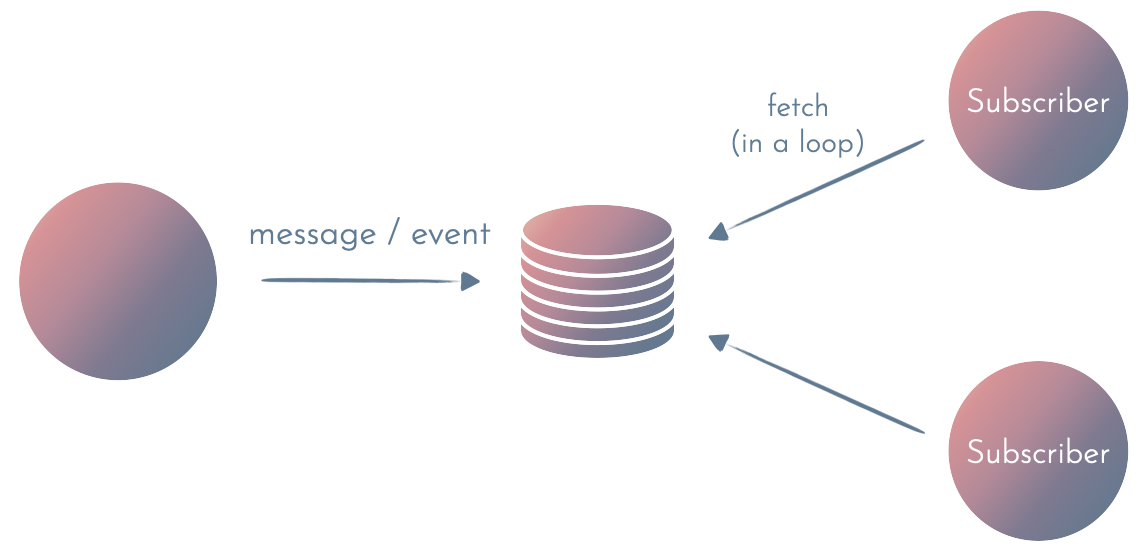

4. Same database for events + smart consumer with polling

If you need every event to be processed in an async environment, you need some kind of persistent storage.

The first and simplest option is to use a single database for data and events. Then, you can have multiple subscribers fetching the data and processing the events asynchronously.

Benefits of this approach include:

- Low operational cost - you don’t need to add any additional infrastructure.

- The same database for data and events means it’s easier to maintain consistency since you can save events in a transaction. There’s no chance of “orphaned” events and no risk of not saving an event when something happens.

Drawbacks of this approach:

- Harder to scale for multiple services because of the coupling to the same DB.

- Harder to scale if the data exceeds a single DB.

- Each subscriber has to implement the logic to fetch the events, keep track of which events it’d already processed, and handle deduplication of events. This can be a lot of repetitive work for a larger system.

- Polling for events in a loop can have higher latency.

Alternative: Use Listen/Notify

You can modify the following approach to limit the number of queries done by polling the DB for new events. If you use PostgreSQL, you can use Listen/Notify to notify subscribers of new events. This way, you only have to ask the DB once (at startup) for the events missed by the subscriber:

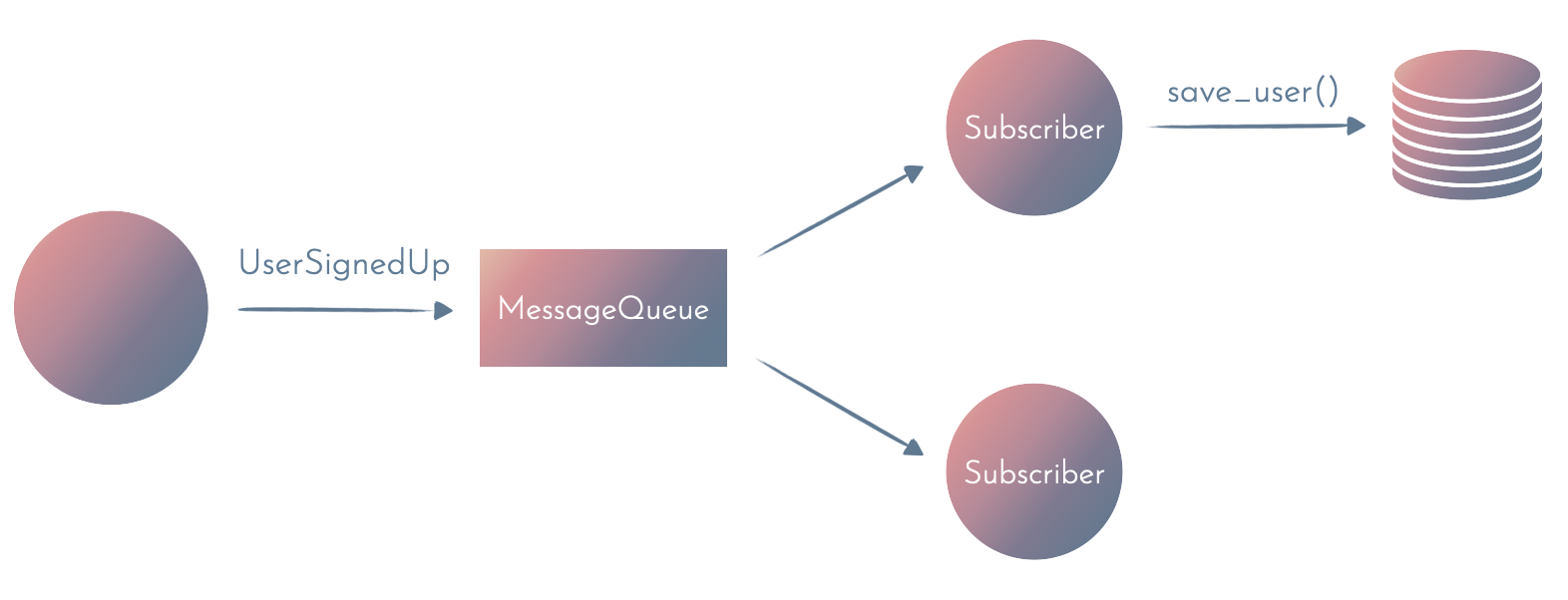

5. Events in separate DB/message queue

Once you use a lot of events, or you have multiple services, you will probably use a separate message queue for events. Examples include:

- RabbitMQ

- Amazon SQS

- Google Cloud PubSub

- Kafka

- EventStore

(While there are many differences between them, it’s way out of the scope of this article to describe them.)

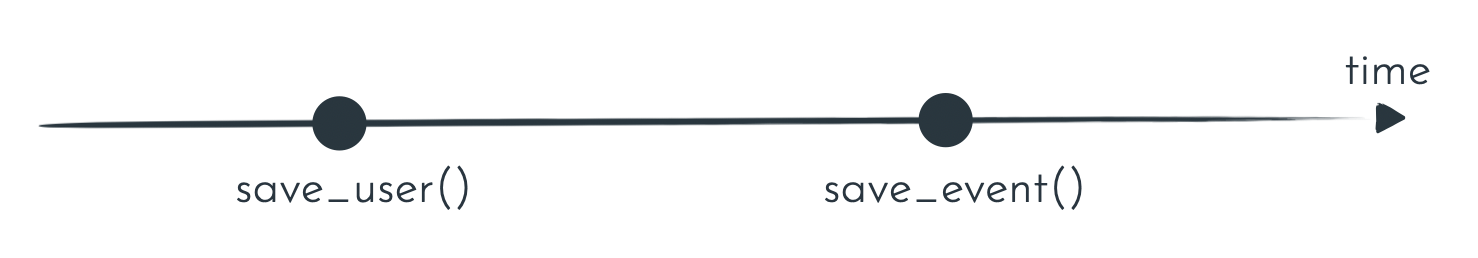

The major drawback of this solution is that you can no longer rely on DB transactions to maintain consistency between your data and the events.

Consider the example:

defmodule Accounts do

def sign_up(params) do

user = save_user(params)

event = %UserSignedUp{

user_id: user.id,

name: user.name,

email: user.email

}

:ok = save_event(event)

{:ok, user}

end

end

There’s no guarantee that the user and the event will be saved atomically.

If anything goes wrong before those two function calls (or the second one fails), the event is gone forever.

One way of dealing with this is to treat events as a source of truth.

defmodule Accounts do

def sign_up(params) do

event = %UserSignedUp{

user_id: user.id,

name: user.name,

email: user.email

}

:ok = save_event(event)

{:ok, event}

end

end

You might have heard about this pattern as Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS). The biggest challenge with this approach is that we’re now in the realm of eventual consistency. The user will eventually be saved in the database, but there’s some unknown delay. CQRS and eventual consistency make the code more complicated at the cost of lower operational coupling.

The important conclusion is that everything is a trade-off and there’s a price to pay for everything. You might lower the operational coupling by introducing a separate message queue, but the price for that is more complicated code and higher operations and infrastructure cost.

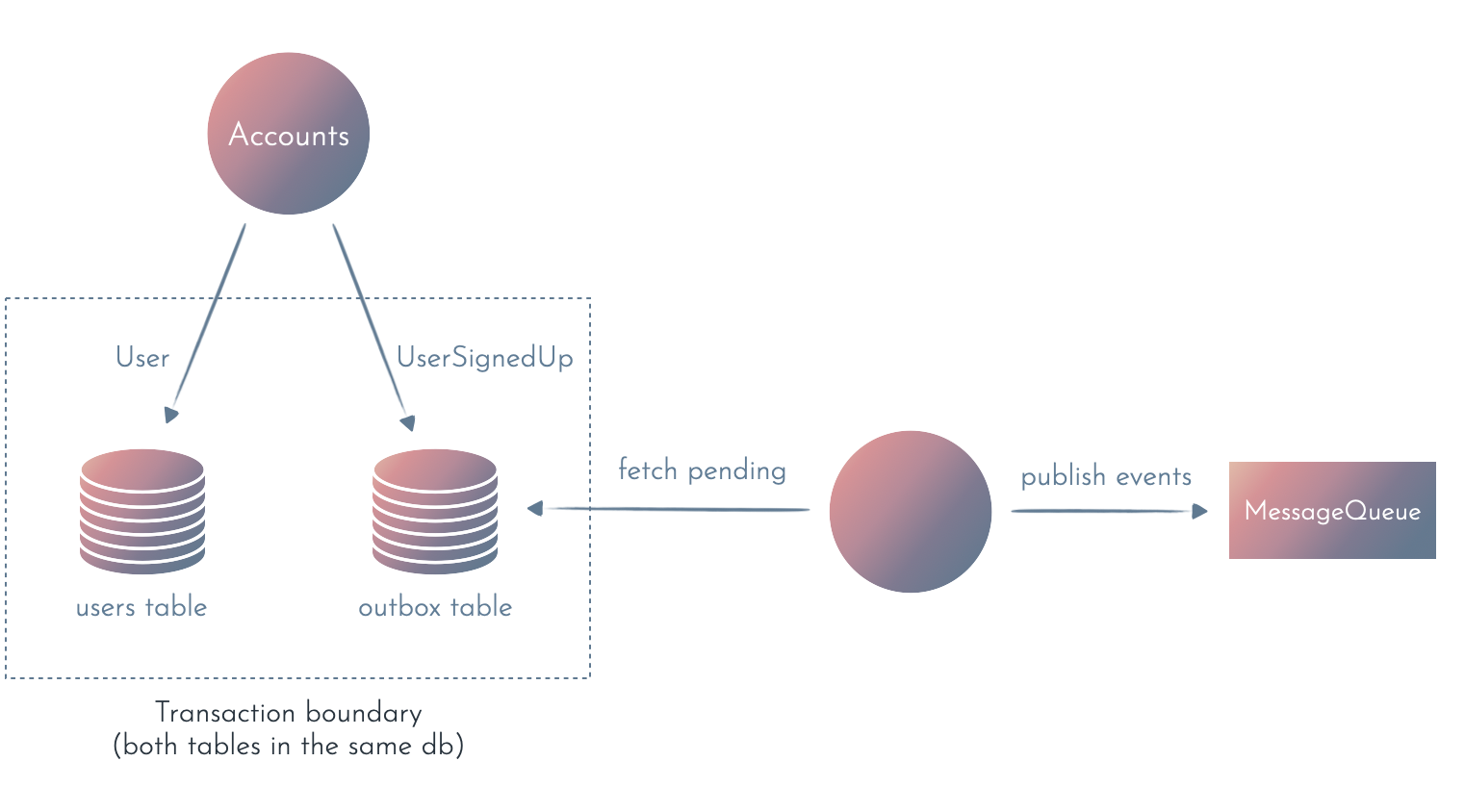

6. The outbox pattern

You can use the outbox pattern when you use events for integration and not as a source of truth, but you cannot lose any events.

The Outbox pattern relies on having an outbox table in the same database as the data. We use a DB transaction to atomically save the data (the user) and the event. A separate process reads the outbox table in the background, publishes the events to the external message queue, and deletes the events from the outbox.

Outbox pattern guarantees that each event will be published at least once, which means that we still have to make sure we can handle duplicated events (but this is a good practice anyway since most message queues have at-least-once delivery semantics).

Performance warning

It might be tempting to use asynchronous processing to make the system “faster” by doing some of the work after returning a response to the client. Unless you know what you’re doing, don’t do that.

Doing work in the background doesn’t make it faster. It only hides the work from the client.

Synchronous calls serve as automatic back pressure. Since the clients wait for the response before making new requests, the server does only as much as it can handle. As the workload increases, so do the response times - which means that each client sends requests at a lower frequency.

Synchronous processing allows your system to slow down gracefully without collapsing. The system slows down, but it doesn’t crash.

If you do some work in the background, the clients can start sending the next requests much faster, leading to the server accepting more work than you can handle. It’s a nightmare to debug since the feedback is much slower, and it’s hard to track the source of problems by looking at your metrics.

Unless you know what you’re doing, have great monitoring, and measure real traffic, don’t use asynchronous processing to make your system faster.

Conclusions

There is no silver bullet. Dealing with events is a challange and each way has its trade-offs.

It’s tempting to treat it as a purely technical problem. But it’s not. The trade-offs of each solution can have a serious impact on the stakeholders of the system. Before you make any decision, you understand the constraints and context of your problem domain.

References

- https://microservices.io/patterns/data/transactional-outbox.html - a great description of the outbox pattern

- Martin Fowler has a great article about different meanings of the phrase “Event-driven”. A must-read.

- In this article, Kamil Lelonek shows you how to use LISTEN and NOTIFY commands from Postgres in Elixir.